When UK Government hosted a two‑day "seagull summit" this spring, attendees expected solid solutions to the growing problem of aggressive swooping birds. Instead, participants walked away calling the gathering a "sham" and a "frustrating waste of time" after being handed out what many described as cartoonish deterrent tips.

The summit, organized by the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra), aimed to bring together local council officials, coastal business owners, and wildlife experts to discuss practical steps for reducing seagull‑related incidents on the UK’s busy promenades. Details on the exact venue and date remain scarce, but sources say the event unfolded in a conference hall on a seaside town that regularly battles gull‑related complaints.

Why Seagulls Have Become a Public‑Safety Issue

Seagulls, once harmless beach scavengers, have increasingly turned aggressive in densely populated coastal areas. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) reports a 28 % rise in incidents where gulls dive‑bomb tourists for food between 2019 and 2023. The National Health Service has logged over 3,200 minor injuries linked to bird attacks, most of them bruises or eye irritation from feathery strikes.

Local councils, especially in towns like Brighton, Bournemouth, and Whitby, have spent millions on fines for littering and on costly “bird‑proof” infrastructure. Yet the problem persists, prompting Defra to convene the summit in hopes of a coordinated national strategy.

What the Summit Actually Said

Participants were presented with a three‑point “quick‑fix” plan:

- Walk around public areas waving your arms to appear larger and deter gulls.

- Draw a pair of eyes on takeaway food containers to make the birds think they’re being watched.

- Use portable, low‑frequency sound devices during peak feeding times.

Sounds simple enough, yet critics argued the measures are more gimmick than science. “Waving your arms is not a deterrent; it’s a distraction at best,” said Dr. Laura Bennett, an avian behaviour specialist at the University of Exeter.

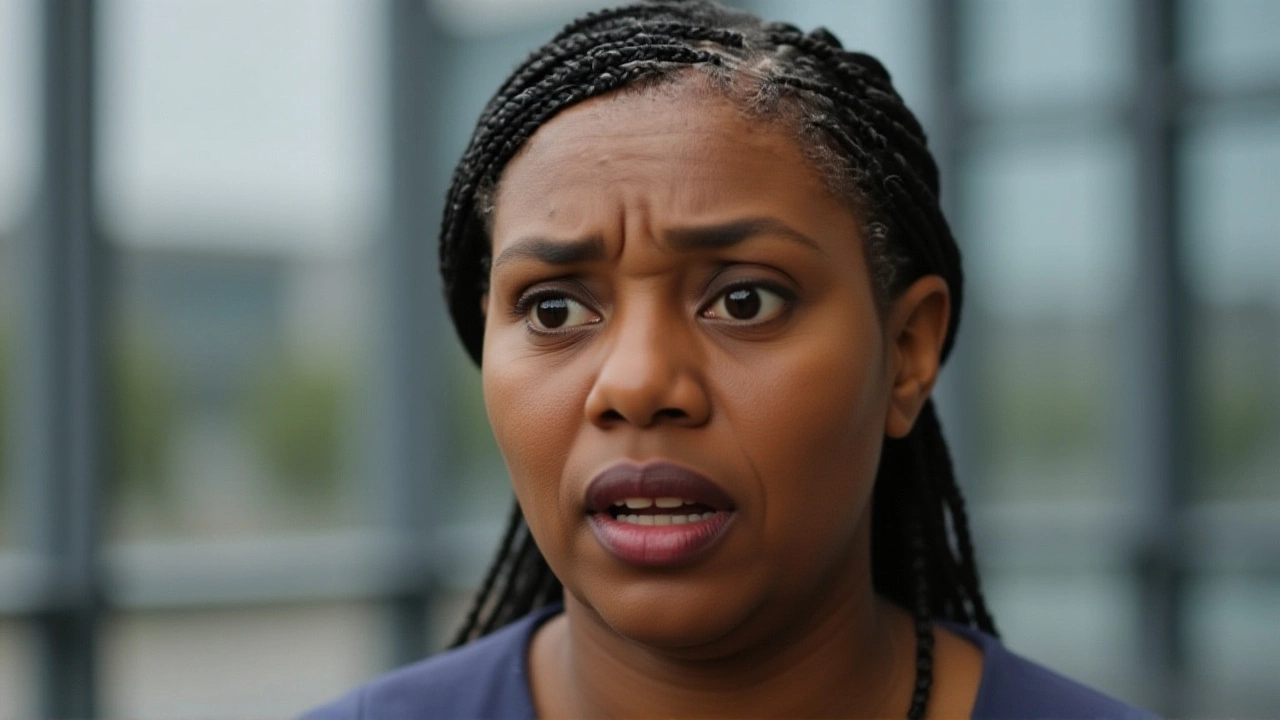

During a breakout session, Mr. Alan Hughes, a council member from a coastal town in the United Kingdom, voiced his frustration: “We’ve already tried signs, fines, and even nets. Hand‑out pamphlets that say ‘draw eyes on your fish‑and‑chips wrap’ feels like a joke.”

Reactions From the Front Lines

Local business owners were especially vocal. Sarah Patel, who runs a beachfront café, told reporters, “Customers are scared to eat outside because a gull can swoop down in a split second. Advising them to doodle eyes on their takeaway boxes does nothing to protect our reputation—let alone our revenue.”

Environmental NGOs also weighed in. The RSPB’s spokesperson, Tom Jenkins, said, “Effective gull management requires long‑term habitat modification, not fleeting gestures. This summit missed the mark on science‑based solutions.”

Broader Implications for Government‑Led Wildlife Initiatives

Beyond the immediate disappointment, the summit highlights a growing disconnect between policy‑makers and community stakeholders on wildlife issues. When the government rolls out top‑down advice without robust field testing, it risks eroding public trust.

Historically, the UK has seen similar mismatches. The 2015 “Pigeon Control Programme” drew criticism for relying on public‑distributed repellents that proved ineffective, leading to a costly policy reversal the following year.

Experts suggest that a more collaborative approach—pairing scientific research teams with local councils to pilot interventions—could yield better outcomes. Dr. Bennett recommends a “tiered response” that starts with data‑driven risk assessments before issuing blanket public directives.

What Comes Next?

Defra has promised to release a follow‑up report within six weeks, stating that the summit’s feedback will “inform a revised action plan.” However, no concrete timelines for new measures have been announced.

Meanwhile, coastal towns are likely to continue experimenting with on‑the‑ground tactics. Some are testing non‑lethal visual deterrents like reflective tape and predator‑shaped silhouettes, while others are exploring waste‑management reforms to cut food availability for gulls.

Background: Seagull Behaviour and Management History

Gulls are opportunistic feeders with highly adaptable foraging habits. Over the past two decades, a surge in outdoor dining and takeaway consumption has created abundant food sources, encouraging bolder behaviour. According to a 2022 study by the University of Manchester, gulls that habitually feed on human waste develop a ‘learned aggression’ pattern, increasing the likelihood of swooping incidents.

Past governmental attempts to curb the issue have ranged from strict littering fines to the installation of “bird‑spikes” on ledges. While these measures have occasionally reduced nesting sites, they seldom address the root cause: easy access to food. The upcoming policy revisions will need to balance ecological considerations with public convenience.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did the government think waving arms would deter seagulls?

The advice stems from anecdotal observations that sudden movements can startle birds. However, scientific research shows gulls quickly habituate to such gestures, rendering the technique largely ineffective in the long term.

Who is responsible for creating a more effective gull‑management plan?

The Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) leads national wildlife policy, but implementation requires coordination with local councils, coastal businesses, and wildlife experts to ensure solutions fit regional contexts.

What alternatives to the summit’s suggestions exist?

Researchers recommend habitat modification (e.g., removing roost sites), improved waste‑segregation, and employing visual deterrents like reflective tape or predator silhouettes, all backed by field trials that show measurable reductions in gull attacks.

How does this issue affect tourists and local economies?

Aggressive gulls deter visitors from outdoor dining and beach activities, leading to revenue losses for cafés, hotels, and seaside attractions. In regions heavily dependent on tourism, even a modest dip in visitor confidence can translate into thousands of pounds lost each season.

When can we expect new guidance from Defra?

Defra has pledged a detailed follow‑up report within six weeks of the summit, but a comprehensive, science‑driven action plan may take several months as pilots are evaluated and stakeholder feedback is incorporated.