In Russia, the line between legal and illegal escort services is thinner than most people realize. It’s not about prostitution alone - it’s about how the law interprets companionship, payment, and consent. Many assume that if no sexual act is explicitly agreed upon, then it’s harmless. But Russian courts have ruled otherwise. A woman offering dinner and conversation for money? That’s not illegal. But if that same woman meets a client in a hotel, even without physical contact, she can be charged under anti-prostitution statutes. The system doesn’t care about intent. It cares about context.

Some clients turn to international services for clarity, like escortparis, where regulations are clearer and enforcement more predictable. But even those who seek alternatives abroad often return to Russia, drawn by familiarity, cost, or the thrill of operating in gray zones.

What the Law Actually Says

Russia’s Criminal Code doesn’t ban escorting outright. Article 240 targets organizing prostitution - not the act itself. That means the person arranging meetings, taking a cut, or advertising services is the one at risk. The escort? She’s often treated as a victim, or worse, as a nuisance. Police don’t arrest escorts for selling sex. They arrest them for loitering, public disorder, or violating migration rules if they’re from another region. It’s a legal shell game designed to avoid direct confrontation with sex work while still controlling it.

In Moscow and St. Petersburg, raids target apartments and hotels. In smaller cities, escorts are quietly pushed out of public spaces. There’s no national registry, no licensing, no safety protocols. One escort in Yekaterinburg told me she changed her phone number every two weeks because her last one was traced through a client’s complaint. She didn’t report the harassment. She knew the police wouldn’t help - they’d ask why she was doing it in the first place.

Social Stigma Runs Deeper Than the Law

The real punishment isn’t jail. It’s isolation. Russian society doesn’t just disapprove of escort work - it erases the people who do it. Families cut ties. Employers fire them on suspicion alone. Even medical professionals refuse to treat escorts without proof of legal employment. A woman I spoke with in Kazan had a broken wrist from a fall. She waited three days before going to the hospital. She feared being reported. When she finally went, the doctor asked if she was a sex worker. She nodded. He wrote “unverified profession” on her chart and handed her a pamphlet on moral rehabilitation.

Men who hire escorts face less stigma - but not zero. In conservative circles, being caught with an escort can ruin a career. One businessman in Nizhny Novgorod lost his government contract after a photo of him leaving a hotel with a woman surfaced online. He claimed they were just friends. No one believed him. The story went viral. His company collapsed within a month.

How Technology Changed the Game

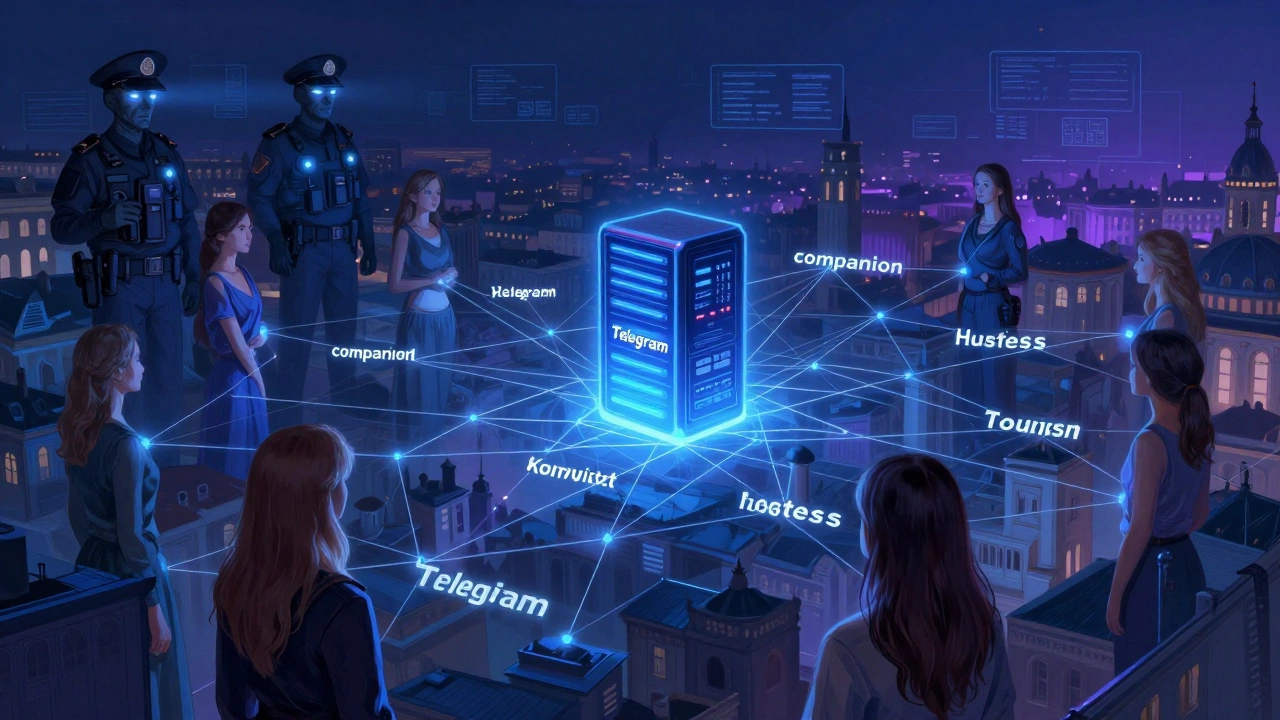

Five years ago, most Russian escorts relied on word-of-mouth or private Telegram channels. Now, platforms like VKontakte and Instagram are the new front lines. Profiles are carefully curated - photos in natural light, no direct mentions of services, captions like “good company for dinner” or “travel companion needed.” Clients message privately. Payments are made via crypto or bank transfers. No cash. No receipts.

But the apps don’t protect you. In 2024, a new federal law required all messaging platforms to store user data for six months. Police now use automated bots to scan for keywords like “meeting,” “hotel,” or “time.” One escort in Rostov was arrested after her Instagram bio used the phrase “professional companion.” The bot flagged it. The police showed up two days later with a warrant.

Some escorts have moved to foreign platforms - but that brings its own risks. If you’re using a service based in France or Germany, you’re still subject to Russian jurisdiction if you’re physically in the country. That’s why some women now work remotely for clients abroad. They video chat. They plan trips. They never meet in person. One woman in Samara makes $3,000 a month this way. She calls herself a “cultural liaison.” She’s never been arrested. She’s never even been questioned.

The Rise of the “Companion” Label

The word “escort” is disappearing from public use. In its place: “companion,” “hostess,” “tourist guide,” “personal assistant.” These terms are legally safer. A companion can accompany you to a theater. A hostess can serve drinks at a corporate event. A tourist guide can show you around the Kremlin. The law doesn’t define what a companion does after the event ends.

Some agencies now specialize in this. They train women in etiquette, history, and conversation. They teach them how to talk about art, politics, and wine - anything but sex. One agency in Moscow charges $500 an hour for a “companion” who’s fluent in three languages and has a degree in literature. Clients pay for the illusion of sophistication. The women pay for the illusion of safety.

But the risk never goes away. In 2023, a woman working as a “personal assistant” in Sochi was arrested after a client reported her for “emotional manipulation.” The police found no sexual activity. But they found text messages where she asked for extra money after dinner. They charged her with “exploitation of dependency.” She got a year of community service.

Who’s Really in Charge?

Behind every escort in Russia is a network - not always criminal, but always controlling. Landlords who rent apartments only to “businesswomen.” Drivers who wait outside hotels and take 20% of the fee. Online moderators who delete posts if they get too suggestive. Even the cleaners in hotels sometimes report guests they suspect are meeting escorts.

There’s no mafia here. No overt gangs. Just a thousand small pressures - the kind that don’t need violence to work. Fear is enough. A knock on the door at 3 a.m. A call from your landlord saying your lease is being terminated. A friend suddenly blocking you on WhatsApp. These are the tools of control. They’re quieter than handcuffs. But they’re just as effective.

Some women try to leave. One former escort in Perm opened a small bakery. She changed her name. She moved to a different city. But every time she applied for a loan or a visa, the background check flagged her old address. She was asked why she’d lived there. She didn’t answer. She stopped applying. She now works under the table, baking pies for neighbors who pay in cash.

What’s Next?

There’s no sign the laws will change. Russia’s political climate is moving further away from tolerance, not toward it. The state wants control, not reform. But the demand hasn’t dropped. It’s just gone underground.

More women are learning to work without meeting clients. More are using encrypted apps. More are refusing to take cash. Some are even starting collectives - sharing information, legal advice, safe locations. It’s not activism. It’s survival.

One woman in Vladivostok started a Telegram group called “Safe Routes.” It’s not about finding clients. It’s about warning each other about police patrols, bad landlords, and clients who’ve been reported before. It has 2,300 members. No one posts their face. No one shares their real name. But they share everything else.

The system tries to silence them. But silence doesn’t mean disappearance. It just means the work moves where no one’s looking.

And somewhere, a woman in Novosibirsk is typing out a message to a client: “I can be your companion tonight.” She doesn’t say what that means. She doesn’t have to. He already knows. And somewhere else, another woman is reading that message and thinking: escoet paris - maybe I should try that.

Then there’s the woman in Omsk who just got her first international payment. She’s never left Russia. But she’s been paid in euros. She doesn’t know how. She just knows it worked. She smiles and writes back: “I’m ready for escort parus.”